Introduction

Have you ever been invited to participate in a “Web-Cam Interview” during a hiring process? If you have, I’m not surprised. This interview method is increasingly common in today’s hiring process. Companies are turning to third party platforms like Hirevue to evaluate potential candidates remotely. Through this method, companies benefit from “90% faster time to fill. 50% improvement in candidate quality. 60% increase in retention.” (quote from Hirevue.com). Sounds great- no? If you are looking to hire, then of course it does! But what about if you are a candidate? Is it great for candidates, too?

In June of 2019, I conducted research with a faculty mentor at the University of California, Irvine, which analyzed my personal user experience with two different “web-cam interview” platforms: HireVue and Gallup. In my essay, not only did I interpret my user experience, but I also investigated the platforms in relation to popular literature in the department of Informatics. This effort led me to conclusions around the User Experience Design and ethical implications of what I come to label “Artificially Intelligent Video-Interview Applications”.

What are Artificially Intelligent Video-Interview Applications?

Video-calling has been around for a number of years. However, most video-calling applications can be boiled down to just folks reaching other folks; people communicating with other people.

This is where a handful of trending Video-Interview Applications are treading new territory in the video-calling landscape. Artificially Intelligent Video-Interview Applications (called AI-VIAs from here on), such as HireVue’s, Gallup’s, and roughly a dozen others, connect you to a web application via internet connection. Once connected, this application allows for person-to-artificial intelligence communication by accessing the persons webcam and microphone. The application uses voice recognition, facial recognition, and software ranking algorithms to collect data on the person as they record (“What is HireVue?”). The data collected is typically purchased beforehand by Human Resources departments within companies and organizations in their quest to find the right candidates for jobs. In other words, AI-VIAs allow algorithms to “read” a video of a person to create data. The primary difference between a video-calling application like Skype and an AI-VIA like HireVue’s, is that users are communicating to their webcam when there is no person on the other end. Where Skype focused video-calling on people seeing other people, AI- VIAs focus on people being seen by an algorithm.

The focus of this essay is to examine the effect the algorithm ingredient has on the flavor of this proverbial bowl of soup. More precisely, this essay aims to analyze the user experience of AI-VIAs and discuss related ethical and legal implications of that experience.

The User Experience: Transparency, Privacy, Autonomy

In this section I will be referring to the user experiences I have had with AI-VIAs as a way of introducing important ideas and questions:

- First, while participating in these interviews, I was unaware of exactly what I was participating in. This part of the experience leads me to the topic of transparency.

- Second, I was unaware of who would be watching, what they were watching, and where that data/information would be used and stored. This part of the experience leads me to the topic of privacy.

- Finally, I retrospectively feel I had no choice but to participate in the interview. This part of the experience leads me to the topic of autonomy.

Transparency

In this discussion, what is meant by transparency is a level of openness and honesty with the user (a belief that a user has the right to know) about processes and information which are pertinent to the relationship between the user and their experience.

It was not at all clear to me during my experiences interviewing with HireVue and Gallup that the interviews were anything more than a web-cam interview. Because the entirety of my application process was similar to every other application process which I had experienced, I had no reason to believe there would be new/additional mathematical models involved in the interview process. The only unfamiliar part of my interview process was setting and format. Answering my questions into a camera while in my living room was new. But I just figured the video was being recorded for later review by hiring managers. However, it was only after researching the topic of AI-VIAs did I learn my video interviews were not necessarily reviewed by people. This understanding only came in retrospect, a long while after submitting my video. Because I am not new to the typical hiring process, I had assumed this was exactly that, a typical hiring process.

I mention all this to make clear that the difference was simply not made apparent. I, the user, was left with a false mental model (which is precisely what User Experience Designers don’t want).

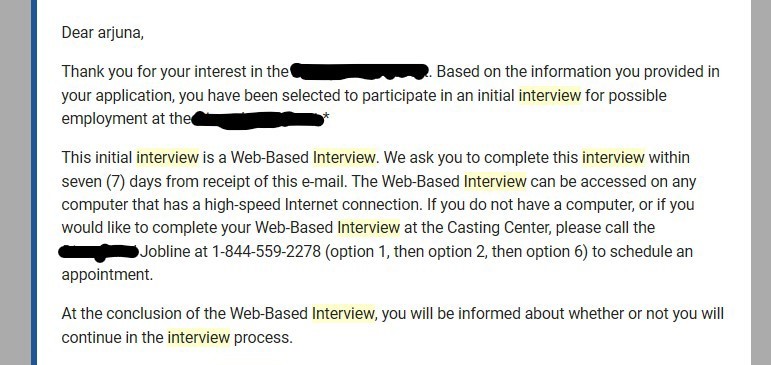

This is arguably because of a lack of transparency on behalf of the company. One specific example of a lack of transparency can be found in the email I received from Gallup regarding my invitation to continue the hiring process. As you can see below (figure 1), the email I received simply refers to my interview as a “Web-Based Interview”. This ambiguous name for an AI-VIA interview is an important contributing factor to this lack of transparency, and is what helps create the false “mental model” in my mind.

In Don Norman’s The Design of Everyday Things, he describes “mental models” as a person’s understanding “of the way objects work” (pg. 38). It is a sort-of cognitive imagining of the functioning of the object. We do this with all types of things, from coffee machines to doors. When you see a door, you imagine how it works (hinges, made of glass, push or pull). We do the same with coffee machines, chairs, TV remotes, everything. The things we do not have mental models for confuse us. In this case, my mental model for my interview was based on the words “Web-based Interview” (as they are individually and as a phrase). I really (hold onto your hats, folks) thought I was participating in a completely normal interview, except based on the web. Norman continues to describe mental models as “essential in helping us understand our experiences, predict the outcomes of our actions, and handle unexpected occurrences” (pg. 38).

Because my mental model was wrong I did not understand the nature of my interview, I could not begin to predict accurately the outcome of where my video recorded answers would end up. However, if the interview had a more transparent- explicit, honest, clear- title which mentioned artificial intelligence, my mental model would have adjusted. A good example of transparent is a credit score generator, such as creditkarma.com. The use of language such as “score” and “credit report”, as well as images which depict what the user can expect the report to look like, helps the user create an informed mental model. Thanks to this transparency, it is likely the user’s mental model includes the understanding that there are data-driven operations working in the background. They likely have accepted there is “invisible” information being parsed, data being retrieved, and numbers being crunched.

When an AI-VIA is labeled a “Web-Based Interview” a person’s mental model is more likely to resemble something related to using Skype. One may assume the video will be recorded for review by a person at a later time, which likely does not consider facial or voice recognition working invisibly in the background while they look into the camera. I would have welcomed an upfront section of this email which briefly defines the use of algorithmically collected data, and a less ambiguous name, even if only for the sake of providing the user with enough knowledge to decide whether or not they would like to participate in the interview. We will look deeper into the ethical and legal implications of this lack of transparency later in this essay.

Privacy

At the bottom of my email from Gallup (figure 1) is a link, which led me to a landing page to start the (roughly 40 minute) process of my “Web-Based Interview”. On that page, there is a hyperlink which leads to Gallup’s Privacy Policy page. Similar to many other privacy policies you may have seen, it discusses how they go about collecting things like your “Personal Information”, as well as what they do with that information- advertisements, cookies, etc. However, it is worth noting I did not find any mentioning of the Gallup company’s use of algorithms within their interviews. Furthermore, the privacy policy is not clear about what specific information was gathered during the Artificially Intelligent Video Interview. Because the privacy policy is limited- ambiguous enough to be left open to interpretation- to more standard privacy issues related to standard internet browsing (i.e. name, email, cookies, etc.) I can not be sure what non-obvious information was retrieved (discussed later in greater detail).

When reading the HireVue Privacy Policy, the concerns are the same. HireVue seems to function in the realm of AI-VIA services (unlike Gallup whose services seem to be more broad). Therefore, HireVue does have a privacy policy which is geared toward AI-VIAs. Yet, sadly, it is still riddled with ambiguity.

One of the key issues with these documents, and this is crucial both to the user experience and for ethical and legal reasons, is an out of date definition of “Personal Information”.

“Personal Information” is no longer (and arguably never has been) descriptive enough. It does not apply, and following with a handful of ambiguous bullet points which cover roughly everything sincerely does not help. What I am getting at is, with AI-VIAs “Personal Information” is not a transplant-able term. It can not be simply transplanted into the new technology of today. Data gathered from a user surfing the web is just not the same as data gathered from the features of a person’s actual likeness in a video. When an algorithm is gathering data during an interview it may be reading anything from eye color to voice fluctuations, whereas data scrubbed from web surfing is often IP Address, email, browsing activities. These are different types of information with different usage implications. With this lack of an adequate definition of personal information, many questions around privacy remain unanswered.

Among the more basic questions like whether or not algorithms are indeed checking for identity factors such as age, skin tone, etc. (which could be a problem in the context of an interview), answers to deeper questions remain unanswered, such as: Does an algorithm collect data on what is in view of the webcam behind the user? If so, would data be collected on people behind the user (even though they have not provided consent)? Would data be collected on objects or people if I am in the privacy of my home? Does the algorithm see a user’s bong in the background, religious symbols on their desk, family photos on their walls?

These questions and concerns, from the perspective of a user, present potential privacy issues which are unique to AI-VIAs. With an out of date model for privacy policies- specifically what defines personal information in the video interview context- and with an unclear description of what data from a video interview is collected, saved, and shared, a user cannot reasonably assess whether or not their personal and legal boundaries of privacy are at risk. The ethical and legal implications regarding this are at least concerning.

Note on Current Research

Before we dive into the final issue of autonomy, it is worth mentioning that there are other issues outside of what is in the scope of this essay. The issues I experienced while interviewing with AI-VIAs- transparency, privacy, and autonomy- can be coupled with well researched and argued issues and questions surrounding big data, algorithmic bias, and machine bias. Since these new forms of interviews are utilizing algorithms and other mathematical models, they are subject to the same issues presented in said research. Such issues include those presented in Cathy O’Neil’s “Weapons of Math Destruction”. Published in 2016, O’Neil presents thorough argumentation concerned with just how much can go wrong when inscrutable mathematical models (such as those used in AI-VIAs) are working ubiquitously in the background to inform human decision making. O’Neil discusses a variety of cases where algorithms have negatively impacted “freedom and democracy”. A specific example can be found in chapter 6, when she addresses discrimination when algorithms and other mathematical models have been used in the past to speed up hiring processes. She discusses a failed use of mathematical models in the 1970’s at the admissions office of St. George’s Hospital Medical School (O’Neil 90-101). During this discussion, she writes:

“The job was to teach the computerized system how to replicate the same procedures that human beings had been following. As I’m sure you can guess, these inputs were the problem. The computer learned from the humans how to discriminate, and it carried out this work with breathtaking efficiency.” (pg 67)

With the information O’Neil presents in her book of the ways in which these mathematical models have been found to be discriminatory, racist, biased, inaccurate, dehumanizing, or simply unethical, one may reasonably decide they do not wish to be judged by such means. This will Segway us nicely into our final topic within the user experience category

Autonomy

Autonomy can be defined as “freedom from external control”, or “the right or condition of self-government”. The definition which is most interesting in relation to our discussion comes from “Kantian moral philosophy”. Here, it is defined as “the capacity of an agent to act in accordance with objective morality rather than under the influence of desires” (“Economic Autonomy”, medium.com). In “figure 1” (the image of the email I received by Gallup inviting me to participate in the interview) Gallup describes my options for opting out. Here is what they say:

“If you do not have a computer, or would like to complete the Web-Based Interview at the Casting Center, please call… to schedule an appointment.”

As a user, it is not clear whether or not I can actually decide not to participate (unless I refuse by not responding). The above quote seems to be an attempt to provide me with an option to connect to the AI-VIA while I am not at home. There may be some comfort in doing the interview in the “casting center”, instead of in my private space. Perhaps also I could call and ask to opt out of participation. Even if that is the case, though, there would certainly be fear of losing the opportunity to get hired just in making that call. Still, it is a welcome attempt at protecting the privacy of the user, as well as offering them some aspect of choice. On the other hand, one can point out this could barely be called an option to not participate. In fact, there was no such option made explicitly clear. This poses the problem where if my desire was to move forward in the hiring process, then it seems like I must participate.

This is a conundrum, because it could be in adversity to my autonomy. If in my knowledge of the history of the mathematical models that drive AI-VIAs I decide I morally object to their use, and therefore wish to try not using them, then I am faced with a show stopping dilemma. Do I continue the process in hopes of getting the job? In correlation with Kantian moral philosophy’s definition of autonomy, do I sacrifice my “objective morality” to the “influence of desires”?

Stepping deeper, not having an opt out is an issue of both autonomy and privacy. Is a person’s personal information truly shared at their discretion if they must relinquish it to AI-VIAs of potential employers in order to be hired? Since employment is connected to fundamental needs such as cost of living and health insurance, does one really have a choice but to share their personal information?

Ethical Implications

My hope is that questions like these may raise some alarms for developers. The ethical implications of the questions I have raised, and will raise, are critical developer questions. Further, these issues of transparency, privacy, and autonomy in AI-VIAs are overlapping. With the effect of a cascade, implications surrounding transparency spill over into implications around privacy, privacy spills into autonomy, and so on. One interesting example of this cascade effect is well represented in a quote found on the HireVue website:

“The last thing a potential employer wants to see is a pile of dirty clothes in the background!” (Blog post on HireVue.com)

First of all, it is easy to disagree “this is the last thing a potential employer wants to see”. This is obviously an overstatement. Although, perhaps, the extremity is purposeful, as to suggest playfulness. This may be the case, but regardless, in light of the discussion of privacy and autonomy we have been having, this becomes a contentious suggestion. The idea implied in this quote raises ethical questions around autonomy and privacy: this quote is an invasive and controlling sentiment which could reasonably be seen as downright unethical.

When a potential employer (not even an employer, but potential employer) is able to quasi-require virtual access to the private space of one’s home, where a person’s autonomy and privacy is legally protected most, and then pass judgement about whether or not that person is employable based on what is within that space, then it is safe to say we have blurred- or lost sight of- the boundaries of privacy. Again, this is especially true when I am unable to opt out of participating. Moreover, there is additional concern when there is uncertainty surrounding what information is being collected, and where and how long it will be stored.

It is important to note, this is not an argument against companies getting to know candidates through reviewing their backgrounds. Where it is generally accepted, and understandable, for a candidate’s social media content to be reviewed by potential employers because it is public information, we should feel ethically compelled to argue against the review of information which is not public. At the top of the list of things which are not public is the space within my home. The ethical question being posed becomes about where we, employers and employees, draw the line between open for review and not open for review. In what space can a person expect to be “left alone” by potential employers? As AI-VIAs become more and more popular, it becomes increasingly more important both ethically and legally that the answer to this question, and other questions like it, be defined.

Here is a list of some other important ethical and legal implications:

Ethical and Legal Implications of Discrimination: As mentioned in the Cathy O’Neil quote earlier in this essay, algorithms run the risk of perpetuating bias. The ethical implications of implementing these algorithms into the hiring process comes with important questions of what moral principles companies are using to guide their behavior. A concern of valuing efficiency over fairness is a reasonable concern to bring up. Furthermore, companies run the risk of legal action due to these biases being embedded into their hiring process. Since discriminatory practices in employment are illegal in the United States, a company must think deeply about the risk they are taking in utilizing these algorithms in the hiring process.

Ethical and Legal implications of “Forced” Participation: As mentioned earlier, it is unreasonable for a person to become ineligible for certain jobs because they decide not to interact with AI-VIAs. For this reason, companies would be morally obligated to consider allowing a candidate to opt out. Without an opt out, this could be speculated as a form of discrimination.

Ethical implication of Dehumanization factor: In some ways, it could be viewed as unethical to quantify complex human characteristics/capacities in a data or list format. Currently this is just questionable behavior morally. Thinking futuristically, though, the tactic of quantifying human characteristics in a data or list format could be (and has been) used against a person’s, or groups of people’s, own best interest.

Ethical Implication of Pervasiveness: Depending upon what data is collected by AI-VIAs, this could be more or less unethical. Personal Identifiers like age range or sex could be argued as harmless data. On the other hand, data like specific answers to interview questions could pose harm when pervasive, especially if shared with other potential employers. Ultimately, in order to function ethically, it must be clear what data is being collected and shared. Further, the user would ideally have control over that data. At this time, this is not the case.

Conclusion

In conclusion, designers of AI-VIAs may be stomping on eggshells. Without improved transparency, the user’s mental model will remain inaccurate. Without an accurate mental model of their experience, the user cannot make a reasonable or accurate assessment of privacy risks. If the user is unable to- or unaware of how to- opt out of the interview, a user may feel forced to forfeit their private information, or feel forced into participation. With this in mind I make some loose suggestions below about how the user experience may be adjusted:

- Improve transparency with clarity of language (i.e. instead of “interview” use a word like “screening” or “score”).

- Improve transparency by making the use of algorithms explicit (i.e. describe through email).

- Improve privacy by reworking Privacy Policy documents (i.e. what information is gathered, where does it go, how long is it saved).

- Improve the user’s autonomy by allowing the user to opt out (i.e. allow them to call the host company or provide an “opt out” button to the user).

I would love to hear reactions to this- longer than usual (thanks for hangin’ in there!)- article. Feel free to leave comments or contact me via email or socials.

As always, thank you so much for reading.

Cheers,

Arjuna Noah Paul Leri

Leave a comment